Humming

I recently took six 12th graders on a marine biology field trip to Hermit Island in Maine. As the final dregs of summer transitioned into fall, my students and I spent several days immersed in tide pool ecology labs. Armed with field guides, we got to know the residents of these tide pools well; their lab notebooks soon filled with common and scientific names for various species of barnacle, seaweed, and hermit crab.

Particularly abundant were the periwinkles–marine snails–who oozed and sludged across nearly every available square inch of substrate. Don’t worry too much if you hear a crunch underfoot, my students and I were told by the program’s more experienced returning faculty. Most of them will mend their shells and be fine.

The evening after the first lab, a colleague and I swapped stories from our separate lab groups’ adventures. I shared my students’ triumph in finding a tiny anemone, a rare sight in that particular spot, after an hour of fruitless searching. My colleague in turn told me about a trick she had learned a few months prior. If you hum to the periwinkles, she said, they will come out of their shells!

I was enthralled. It was already shaping up to be one of the most joyful weeks I had had in a long time. Now you’re telling me there’s a sound-related phenomenon I happen to be in the perfect place to investigate?! I thought. It was as if my birthday had come early.

The next day, I tested the theory. I situated myself just out of earshot of any students who might see me engaging in the silliness of serenading a snail. I plucked an unsuspecting periwinkle from a nearby rock. It immediately retracted into its shell, hiding.

I hummed.

Quietly, at first. Then a little louder, once I was confident no students were staring at this embarrassingly earnest display of wonder-seeking. I varied my pitch, giving my snail a range of higher and lower frequencies to respond to.

And, slowly but surely, it emerged. At first, only a mere hint of its muscular head-foot extended beyond the shell opening. But soon enough, two tentacles poked and felt and unfurled their way out into the open. Seemingly, the humming trick had worked!

Video description: my hand holding a periwinkle, a snail with a brownish green and purple shell. I am humming to the snail, which emerges from its shell and pokes its tentacles out into the open air.

I made my rounds to each clump of students. They squatted in small groups, scattered across the rocks like a colonial tunicate. I shared the trick with them. The tide pools soon became an open-air concert venue as the students hummed to snails. The hungry wind gobbled up most sounds before they traveled far, but I heard a few exclamations of oh my gosh, it’s working!

I tried it a few more times myself. Reproducibility is a hallmark of good science and I was determined to be a good scientist while I had access to the tide pools. I tested different frequencies and repeated my methods with multiple snails. I’ll admit I may have been somewhat of a menace to my local mollusc community; an overzealous entertainer to that gaggle of gastropods.

And yet each time I saw those tentacles emerge, I wondered if my singing was really doing anything at all.

Was it truly my humming that brought the snails out of their shells? Or would they have ventured out anyways, given enough time? Was I just startling all of those snails for nothing?

Retreat

Snails retreat into their shells to avoid predation. When they feel threatened by a predator (or a big scary scientist), they retract their head-foot, tucking it under that spiral armor.

When you move at a snail’s pace, you must learn to flee while staying in place.

I know a little bit about what that is like. Many of us do. We who have lived through traumatic situations we could neither fight nor physically escape from have had to learn to flee inward into ourselves. We build all sorts of armored shells to protect us and we shelter in place within them. We dissociate. We detach ourselves from emotion. We disconnect from community. Those of us who survive still disappear as best we can. Sometimes, absence in the present is the only way we get a shot at some future presence.

I wonder: was being picked up the scariest thing those periwinkles had experienced all day? All week? Or was that just a typical Tuesday afternoon for them? Was retreating in fear as frequent an occurrence for those snails as it was for me, five years old and cowering in the corner of my bedroom?

The shape of snail

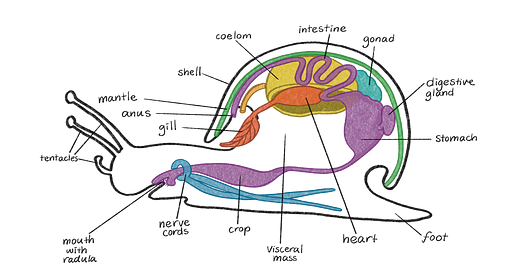

Image description: a colorful, labeled diagram of snail internal anatomy. Drawing inspired by this one from OpenStax Concepts of Biology.

In the Linnean tradition of taxonomy, snails belong to class Gastropoda within phylum Mollusca. Etymologically, “mollusca” refers to their soft body, while “gastro” references digestion and “pod” means “foot.” Anatomically, they are indeed quite squishy under that rigid calciferous shell, and they have a more developed digestive system than the older marine invertebrates that preceded them evolutionarily. In fact, while we may take it for granted in our own mammalian bodies, the fact that snails have separate openings for eating and excreting sets them apart from their predecessors, the sponges and cnidarians.

These and most of their other tissues and organs are covered by a skin layer known as the mantle, which in turn both secretes and is protected by the calcium carbonate (CaCO3) shell that surrounds it. In this way, snails build their own shelter against forces that would harm them.

Their shell is less like a house they occupy and more like a suit of armor they craft themselves. It grows with them and they can often secrete further calciferous material to mend minor cracks in its structure, hence my colleague’s reassurance that the inevitability of stepping on snails should not deter me from engaging with the tide pools.

Contortion

Retreating requires space. In order to tuck one’s head-foot up into one’s shell, there must be space inside the shell reserved for that head-foot to go.

Snails have achieved this through an adaptation known as torsion. While they may appear to exhibit bilateral symmetry to an external viewer, cutting an adult snail in half lengthwise would not result in two functionally symmetrical allotments of internal viscera. This is because their organs have been effectively contorted along their shell’s spiral shape, coiling around the perpendicular axis and leaving space in the center for their retreating head-foot.

Image description: a simplified labeled diagram of snail anatomy before and after torsion, drawn from the top-down, showing just the repositioning of the gills, mantle cavity, and digestive tract (in purple) as they coil around an imaginary axis perpendicular to the snail’s body length.

I think of the ways in which trauma teaches us to re-shape ourselves. Of how it leads us to re-organize our internal ecosystem of manifold parts, the pieces of ourselves we must shelve away or hide or hide from. Of the space we must make to hold what doesn’t feel safe to express to the outside world. Of how none of this effort is externally visible.

Cons of torsion

Torsion is generally considered an adaptation, an evolutionary advantage allowing snails to better defend themselves. However, torsion also presents a serious problem to a snail. Anatomically, torsion places the anus right above the gills. This can lead to some…unfortunate backwash situations, shall we say.

In general, it’s a pretty bad idea to excrete where you eat. It’s an even worse idea to shit where you breathe.

In response, some groups of snails have reversed their evolution of torsion–a process we refer to, creatively, as detorsion.

The ability to hide in one’s own shell thus comes at a cost. Likewise, trauma takes a toll on our physical body. We lose much when we shelve parts of ourselves away for safety, when our fight/flight/freeze reactions become chronic and shove down the potential for more expansive responses to difficulty. Sometimes, we breathe in so much of our own shit that it makes us sick. Our adapted bodymind is also a disabled bodymind.

I have felt significant overwhelm recently in confronting the amount of healing I have left to do. If my own emotional torsion evolved over a near quarter century of trauma, how long will my detorsion take? How much reorganization must I do to feel like my bodymind is more than a cavity to retreat into? How can I make more space for myself?

Armor

Snails are not the only creatures who hide in the shells on their backs. On the drive home, one of my students compared me to a hermit crab. You have a shell that you can retreat into and come out of, they said.

I have been mulling over this comparison since then. It is true that I have moments of both retreating into and emerging from the protective thorniness I have assumed in the past year. But is my armor a mailed garment that hides and protects me, like that of a hermit crab, or an immutable facet of this stage of my being, like a snail shell?

I think this veil of toughness–behind which I hide earnest willing, desiring, and loving–is more akin to a snail’s self-secreted shell than a hermit crab’s borrowed one. After all, I have built this gruff persona with my own two hands. My bodymind dissociates of its own accord to protect me. I shape what scraps of indifference I can conjure up around my soul to convince would-be predators–the entire world, the traumatized bodymind assumes–that I am no more than an empty shell. Nothing to see here. Move along.

I do not borrow my armor. I was not gifted my resilience. This shell is homemade and hard-earned and I did not have to search for one that fits. It grows with me, morphing and stretching as the soft animal of my body pushes against its rigid walls from the inside. It expands as I become more than it is capable of holding. I take on the form of this shell; it in turn constructs the shape of snail.

Emergence

The periwinkle will have to emerge eventually to reorient itself. It cannot do this with its head retracted into its shell. It must risk predation if it ever hopes to reattach itself to tidepool substrate.

The snail will begin this process slowly. It must be careful, testing before committing. But it must ultimately be brave.

This is true of people, too. We cannot find the kind of stable safety many of us have been denied by retreating inward indefinitely; in this state, we have minimal agency to both give and receive love, which I would argue is a critical ingredient for healing.

In her book Braiding Sweetgrass, Robin Wall Kimmerer describes a state of “living awake in the world” (pg. 36). That phrase has stuck with me for weeks. Awakeness in the world is what people and periwinkles both seek when we begin to emerge from our shells. I yearn for that feeling with every fiber of my being and yet putting it into practice involves trust, which terrifies me.

Trust in the good intentions of other people. Trust in my lovability as a flawed being. Trust in the possibility of a survivable future… and maybe even trust in a thriveable one.

I’m not sure I know how to do that yet.

But sure as snails, I am trying.

For nothing

It turns out that as far as science knows, singing to snails, while a charming coastal pastime, does not compel them to come out of their shells any faster. When we see them reemerge, they were already on their way out to check if it’s safe again. I guess I did pick up those periwinkles for nothing.

I am grateful to have learned from them. My students and I now know more about the behavior of periwinkles–their hiding and curious re-emerging–from singing to them than we would have ever learned from a paragraph in a tide pool field guide. But I am sorry that our learning cost them their peace.

I had planned to conclude this reflection with something about the beauty of singing to snails as a manifestation of our human desire to cocreate with our creature kin. Perhaps that is true. But the quickness of the snails’ initial retreat keeps replaying in my head like a looping video. For all the beauty in the world, I cannot ignore the fact that each time I picked up a periwinkle, I scared it. And the next one. And the next. For the duration of my little experiment.

May they–and we–find the courage to emerge again.

Poem

For a Five-Year-Old by Fleur Adcock

A snail is climbing up the window-sill

into your room, after a night of rain.

You call me in to see, and I explain

that it would be unkind to leave it there:

it might crawl to the floor; we must take care

that no one squashes it. You understand,

and carry it outside, with careful hand,

to eat a daffodil.

I see, then, that a kind of faith prevails:

your gentleness is moulded still by words

from me, who have trapped mice and shot wild birds,

from me, who drowned your kittens, who betrayed

your closest relatives, and who purveyed

the harshest kind of truth to many another.

But that is how things are: I am your mother,

and we are kind to snails.